|

About Great Lakes Shipwrecks • Shipwreck Map & Index • Great Lakes Scuba Diving • Posters & Photos • Links • Contact |

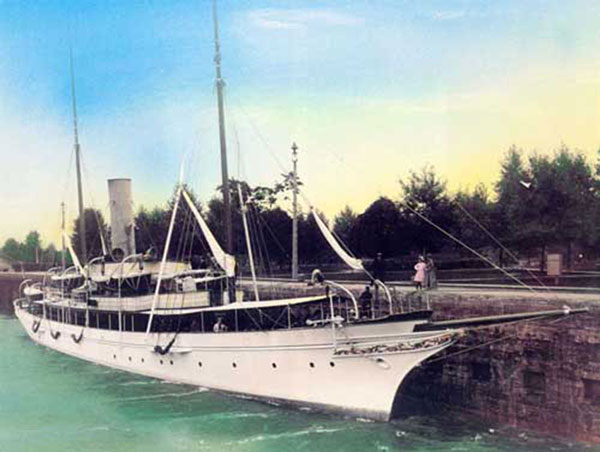

Diving the Gunilda I learned how to use mixed gas in 1993. It was an accident, really. My wife had traded a nitrox course as part of the payment for a dive shop logo design. I had no use for anything other than air back then. As far as I was concerned it had worked just fine on recent dives done on the Samuel Mather at Whitefish Point. Skin Diver Magazine and much of the dive establishment were screaming about the danger of diving mixed gas. Jan told me the course was paid for and I may as well show up. I did. When the nitrox instructor found out I had been on the Mather, he suggested that I learn to use helium. He told me he could not train me but there was a guy on Long Island who could. So on a warm September day I found myself driving to the east coast with a set of double aluminum 100s. A week of long classroom theory followed by blending late into the night introduced me into the magical world of trimix. I went from nitrox in July to trimix in September. Many divers did not believe in the concept of helium back then. They felt it was just not worth the money, or they were comfortable diving deep on air, or they just never got “narked”. About this time a team of American mixed gas guys got permission from the Canadian Government to dive the Gunilda. The Gunilda was a steam luxury yacht owned by Standard Oil investor William L. Harkness. It was built in Scotland in 1897 and considered the finest boat in the New York Yacht Club at the turn of the 20th century. In summer of 1911. the Harkness family and friends were on an extended tour of the north shore of Lake Superior, heading for the small town of Rossport. Coming around the north side of Copper Island at speed, the ship ran high aground onto McGarvey’s Shoal. The shoal is a sheer cliff of rock rising out of 280 feet to within three feet of the surface. A contemporary photo shows the yacht almost completely out of the water. The passengers were eventually ferried to Rossport where they took a train back to New York. Harkness stayed behind to supervise the operation of pulling the Gunilda off the shoal. Much has been written about Harkness refusing to listen to the salvage crew. Whether true or not, the Gunilda flipped on its side during the pull, filled with water and sank in 270 feet. After they walked away and left it there in 270 feet of cold fresh water, rumors started and a legend was born. Soon divers began to dream of cash and precious stones left on the ship in 1911, in spite of the unlikelihood of Harkness’s family and friends, able to pack up their belongings and board a train in Rossport for New York, but leaving all their valuables on the high and dry yacht, in the middle of the north wilderness; but that tends to be the nature of treasure legends. Salvage was first attempted using standard hard hat, then later, open circuit SCUBA. Most found the Gunilda too deep. A few would actually make it. Some would die trying. In the world of deep air, diving the Gunilda was just short of lunacy. During the 1990s much of the mixed gas diving occurred at Whitefish Point. The reason was simple: Whitefish Point had some of the deepest known shipwrecks in the Great Lakes. As divers discovered the power of helium they would come to dive the deep wrecks, especially the Superior City in 270 feet. Among these divers were the few who had dove and filmed the Gunilda. Using trimix they had done something only a well funded commercial operation could do a few years earlier. It was now just another wreck dive. At Whitefish the story was the wreck wasn’t just a good dive; it was the best! I was definitely envious. It would be many years before I would get to the Gunilda. By that time mixed gas was almost mainstream and charters had taken hundreds of divers to the wreck. It was the summer of 2009. Our friend Peggy called to ask if I wanted to do the trip. How could I refuse? It was still “the best”. Five hundred cubic feet of helium, four sets of doubles, a K bottle of oxygen, argon; I loaded it into Peggy’s trailer late on a warm August afternoon. We headed north, stopped at Mackinaw City for the night and pulled into Rossport on the north shore of Lake Superior later the next day. The first dive took place the next morning. The run from Rossport to the wreck was quite short. We meandered through a series of islands and tied to the wreck behind Copper Island. This was not an open lake dive. It would be flat water diving all week. Peggy and l did four dives, and I came to understand how this wreck could be deadly. The Gunilda lies tucked in the shadow of the sheer rock face of the reef. Others have told me that conditions can be really clear, but we had a constant current over the reef depositing silt on the wreck all week. It was dark and silty. Light was gone by 200 feet. While descending down the line on my first dive I thought I had to be close to the bottom when there was another 50 feet of drop before touching the wreck. I couldn’t imagine doing this under the heavy narcosis of air. We had about ten feet of visibility, but it wasn’t hard to navigate the narrow and intact ship. Any place I looked was a photo: the helm and spotlight on the bridge; nav station and chart table; lantern locker; the main salon with fireplace and piano. It’s a unique museum from the gilded age preserved in a cold water grave, a treasure beyond imaginary jewels and cash. In 1980 The Cousteau Society brought the Calypso into the Great Lakes. During exploration of the north shore of Lake Superior, they stopped to moor the Calypso over the wreck. Using their diving “saucer” they were able dive and shoot film. Philippe proclaimed it the most beautifully preserved shipwreck he had ever been on. He said it was “the best”!

The bell on the bow.

The cast bow section below the missing bowsprit with gold leaf.

The forward bow area.

A locker on the port side held back up running lights and lanterns.

A closer view of running lights probably used if the electric generator failed.

This electric search light was pretty advanced technology at the turn of the 20th century.

A shot of the grand salon.

The fireplace in the grand salon.

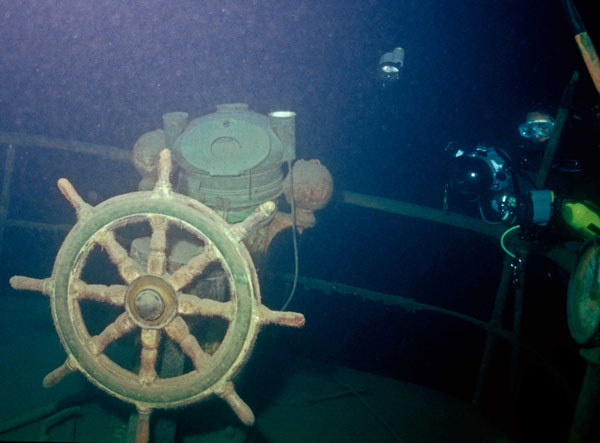

The wheel and binnacle on the flying bridge. The face of the engine telegraph can be seen on the right.

This fan hiding inside a partially open door would provide relief on a hot summer night in the days before air conditioning. |

About Great Lakes Shipwrecks • Shipwreck Map & Index • Great Lakes Scuba Diving • Posters & Photos • Links • Contact